In Judaism, Islam, Christianity, Buddhism and even Scientology stands the "Golden Rule" of Old Hillel

There is the known Talmudic story (Shabbat 31:72 ) about a gentile who came to Shamai and told Hillel: “Convert me to Judaism in order to teach me the whole Torah while I stand on one leg.” Shamai refused and sent him away. The gentile did not give up and went to Hillel with the same request. What did Hillel do? Hillel converted him to Judaism and told him: “What you hate, don't do to your friend.” That's the Torah. The rest is interpretations. Since this sentence is not in the Torah, it is interpreted as a translation of: “Love thy neighbor as thyself.” And Rabbi Akiva states (The Jerusalem Talmud, Nadar 9:4): “This is a great rule in the Torah.”

“Love thy neighbor as thyself” (Leviticus 19:18), which is considered to be the essence of Torah orders when it comes to how human beings should treat one another, has been widely interpreted all the way up to the present day. These few words enriched the Jewish interpretation with an abundance of parables, ranging from the simplicity of scripture through a broad spectrum of interpretations to a question that might interest psychologists: “Do you like yourself?” And what if you don't like yourself? What duty does it apply to you then?

To illuminate this, it is worthwhile to bring some examples of Talmudic scholars and commentators to this order, a viewpoint that reflects their concern for maintaining the dignity of others—in life and death. In the Sanhedrin and in the inscriptions, you read: “‘And you love your neighbor like you’ also means, a dignified death for him!" In other words, even in the hour of his death, make sure not to despise him. Even if he is evil (and there were those who were evil—slander requires evil) and his sentence is death, the form of execution of the sentence must be taken into account not to dishonor the dignity of the sentenced person. And R. Akiva said: “Don't say because I was disgraced, my friend will also be disgraced.”

It is impossible not to briefly mention at least three biblical commentators. The Rambam: “Love thy neighbor as thyself—it is an exaggeration (since no person will love his friend as his love for his own soul.” The Rashbam: “If he is truly your friend. If he is good, but not if he is evil,” and R. Ovadia of Sporno says: “Love your friend in the way you would love yourself if you were to be in his place.” Great commentators like Rashi are satisfied with bringing the words of Rabbi Akiva: “Love thy neighbor as thyself: that's a big rule in the Torah.”

Rabbi Yehezkel Abramsky, with the addition of Ezekiel's vision, interprets the saying with a concrete example: “To repent of one another as he would for himself.” And he adds that a man who marries a woman against his will and other motives, “a woman who is unfair to his nature and temperament,” “because she is unfair to him, becomes hated by him and since she hates him he will harden his heart while she needs a relationship of love and friendship.”

In addition to the reference to Hillel, there are lesser known sources. In the Avot of Rabbi Natan, a 4th-century essay, it is written: “One came to Rabbi Akiva and told him to teach him the entire Torah as one. The rabbi replied that it took our father Moses 40 days and 40 nights to learn it while he was in Mount Sinai, and you ask me to teach you the entire Torah quickly? My son, in essence, this is the entirety of the Torah (the Hebrew translation): Whatever you hate don't do that to your friend. If you do not want to be hurt by another person, you do not hurt him as well.”

If you do not want another person to take your goods, you too will not take goods from your friend as well.

In “Naftali's will,” the following sentence appears: “And no one will do to one another what he did not want done to his own soul.” And another manuscript of the same essay reads: "No one will do to one another what he does not want done to his body.”

The Rule of Old Hallel was accepted by Christians and was called the “Golden Rule of Christianity” and is also prevalent in other religions as well. In the Evangelion it appears twice: in the book of Matthew—"Therefore, all that you desire that others will do to you, you also do it to them since this is the Torah and the prophets”—and in the book of Lucas: “And as you desire to be treated by others, you do to them the same.” These are not the only quotes. In the gospel of Thomas (known as the skeptic), that is not included in the Evangelion, we read (originally in Coptic) “Love your brother as you love your own soul; protect him from any harm.”

Although Judaism and Christianity have contributed greatly to the dissemination of the sublime idea, they are not the first to envision it. Hundreds of years before, we find in the articles (Analects) from Confucius (who lived in the 5th century BC) the following dialogue between the teacher (Confucius) and his disciple (Zigong):

Zigong: “What I don't want others to do to me I want to avoid doing to them.”

Confucius: “You haven't reached this level yet.”

Zigong: “Is there one word that can indicate a person's (true, preferred) behavior throughout his life?”

Confucius: “It's probably mutuality, isn’t it? What you don't want others to do to you, don't do to others.” (Dan Daur, Meng Dza, Jerusalem 2009, p. 391).

About a century before, Thalis (one of the “seven sages”) gives the advice: “We must avoid doing what we have condemned in others.”

Muslims perceive the following rule: “Part of the belief is that (the believer) will ask for his brother what he is asking for himself.” (Courtesy of Prof. J. Friedman), whereas Brahmaism/ Hinduism states (loosely translated): “Do not do to others what would cause you pain if it were done to you” (Mahabharata 5, 1517).

Our earliest citation is in ancient Egypt, and its estimated time is between the 20thand 17thcenturies BC: “Do for the other who may work (in due course) also for you, and thus drive him to do so” (The Tales of the Eloquent Peasant, trans. R.B. Parkinson, London 1991T). This “golden rule” also refers to the “law of mutuality,” which in Latin is referred to as a conduct by: “do ut des” (loosely translated: “I give you so you can give me”). The Baha'i religion, born in the first half of the 19thcentury, recommends to its believers: “Do not treat another soul what you would not attribute to yourself”; and if it is justice you are seeking “Choose for your friend what you would choose for yourself.” And Scientology, which is less than a century old, also has this in its “moral code” (Article 20): "Try to treat others as you would want them to treat you.”

These rules, however, have great importance in Judaism. The following is a story presented in the Baba Kama tract: “This is a tale of one person who was throwing stones from his property onto the public property, and a Hasid saw him doing it. The Hasid said: ‘Why are you throwing from your property to another property that is not yours?’ The person mocked him. The person later had to sell his field and walked in the place he previously threw the stones and he stumbled and fell on the same stones. He said the Hasid was correct.”

A beautiful example of “loving your neighbor like yourself” is the quote from the Jerusalem Talmud (Tractate v. 9, 4) and generally: “Love your neighbor as yourself” (in Aramaic translation): “We say? You will not rise or torment your people.” And here’s an example: “One who cut meat and the knife hurt his other hand. Will you hit back the hand that holds the knife?” Others add to this example the following (a text that is not found in Jerusalem and is allegedly derived from Pythagoras, however we couldn’t verify it) and this is the equivalent of the Jerusalem quote: “If you cut your tongue with your teeth, would you punish your teeth and break them?”

To “love your neighbor like yourself” was added to Rabbi Aryeh Levin’s (unwritten) ruling: “And love for your wife like yourself.” And this is the story: One of his students asked: How should I treat my wife? Rabbi Arya was surprised by the question and answered: “And what is the question? After all, she is like your body, treat her the way you do yourself.” Indeed, when his wife, Zipporah Hanna, did not feel well, Rabbi Aryeh accompanied her to the doctor and said to the doctor: “My wife’s leg hurts us.” (Simcha Raz: Man of a Righteous One, Jerusalem, 1973 p. 101).

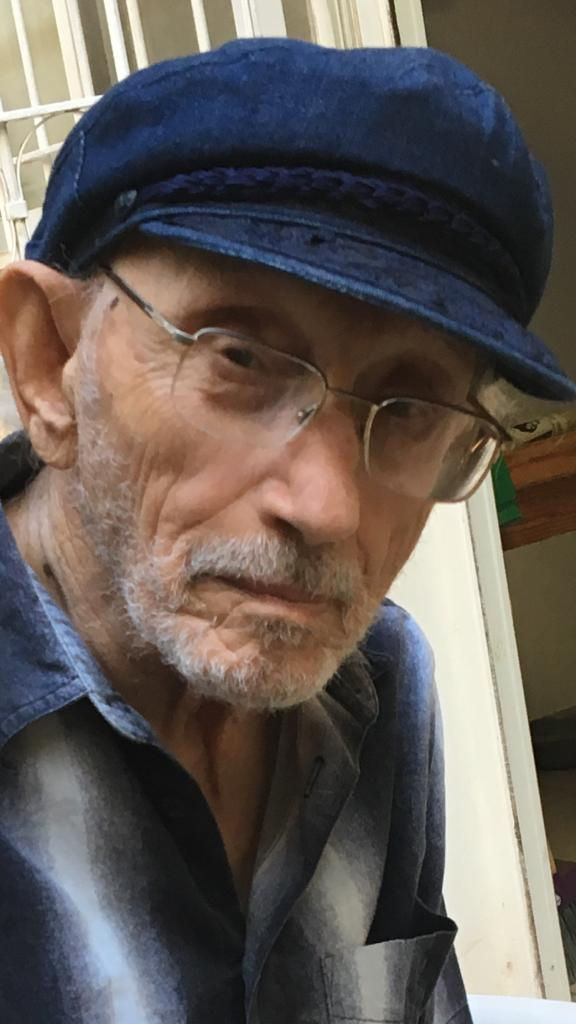

Ben-Zion Fischler

Born 1925 in Bukovina, Ben-Zion Fischler was 16 when his family were deported to the work camps in Ukraine by the Nazis and their collaborators. He survived the Holocaust, unlike many of his relatives, including his father.

When he first went to Israel in 1947 he hardly knew any Hebrew. Self taught, he quickly became a Hebrew teacher for newcomers from post-war Europe, finally becoming the head of the Unit for Teaching Hebrew in the Diaspora and the coordinator of the Council on the Teaching of Hebrew and Committee on Hebrew Studies at Universities Abroad for the World Zionist Organization.

He married Brakha Fischler, a researcher in the Academy of the Hebrew Language, and has two sons. The elder one, Yosef, is called after his grandfather, who died in the camps.

After retirement he dedicated himself to researching and publishing on the origins of famous sayings wrongly attributed to the ancient Hebrew sages. Lives in Jerusalem. This article was originally written and published in Haaretz newspaper in 2010.